In the early days of World War 1, as trench life started to settle in, British soldiers would kill a few minutes of the long stretches between combat by writing home to friends and family. They did so in the millions. To deal with the overwhelming demand, the UK’s General Post Office established an enormous sorting office in London’s Regent’s Park by the end of 1914. It was a maze of stacked sacks, piled on top of each other and stretching out as far as the eye can see, like some sort of forgotten administration room in Hogwarts.

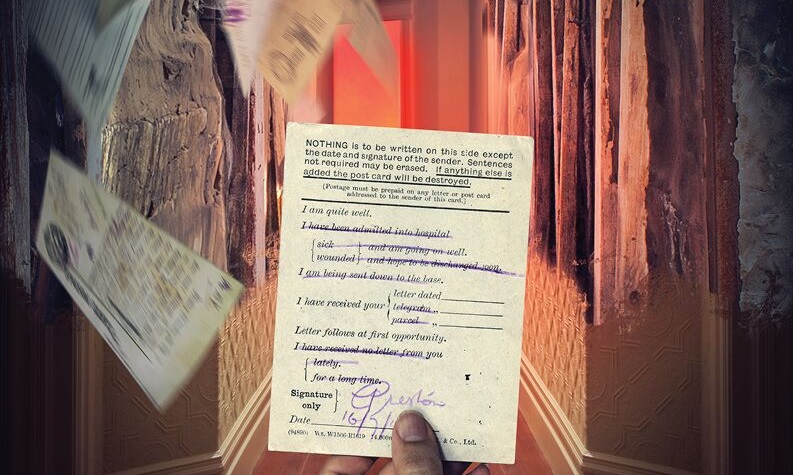

The meeting room of 59 Productions looks like a miniature version of that scene when I walk in to see its latest VR experience, Nothing to be Written. Sprawled across the table are several real letters from soldiers, some of which still bare the pencil markings from where locations and other information was censored out over 100 years ago. But there’s another type of message on the table, too. They look like multi-choice postcards, with several printed statements like “I am quite well” and “I have received your parcel” listed. Soldiers only had to highlight what was relevant to them, then send the card on its way. They were called field postcards.

“At first these look really sinister,” 59 Director Lysander Ashton explains as we sift through a pile of them. “But soldiers loved them. You could send letters but they would have to be censored. These would bypass the censor office and get back home within two days, so it was actually a very immediate way of communicating.”

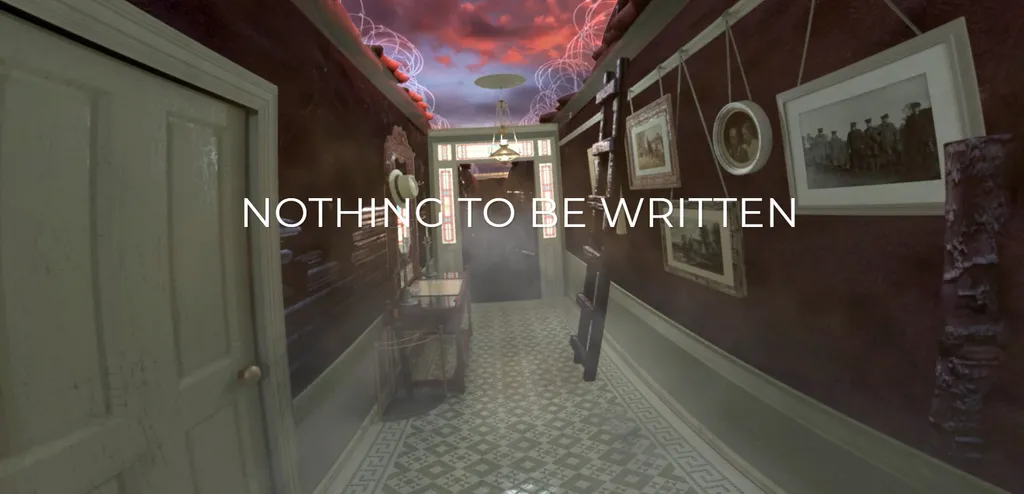

It’s these cards, and the idea of a story behind every automated letter, that form the foundation of Nothing to be Written, a companion piece of sorts to the second movement of a new choral score from composer Anna Meredith, created in collaboration with the BBC as part of the ongoing Prom season. It’s a VR war experience unlike anything you’ve yet seen, trading bullets and bangs for a deeper look at the real lives involved in an unspeakable tragedy. Music from the piece flows throughout as you’re taken on a seven-minute journey that bridges the gap between the frontlines and a card’s final destination through the letterbox of a loved one.

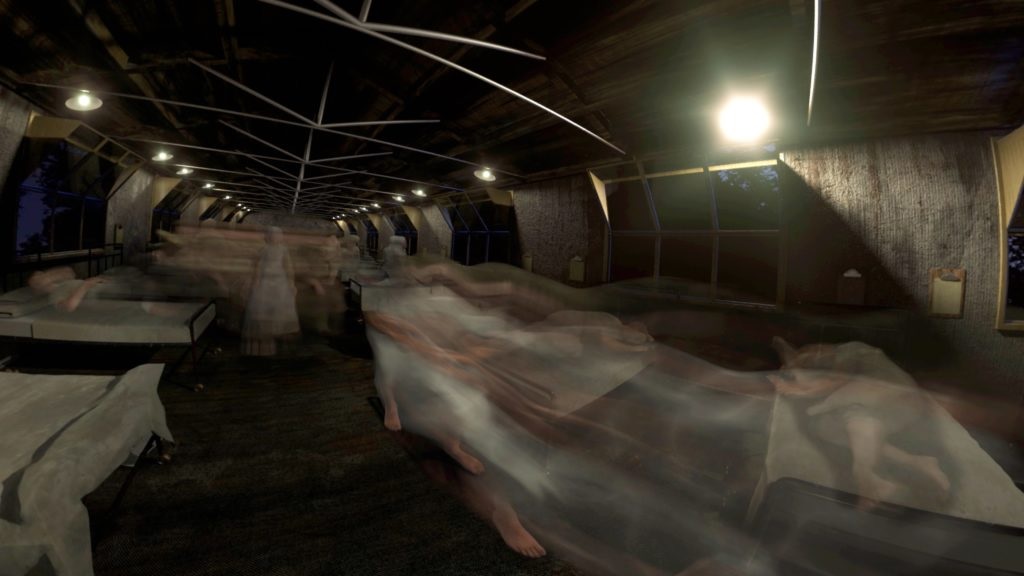

Tonally, the piece is one of the most striking and overwhelming explorations of war in VR I’ve yet seen. It whisks you away from the stuffy confines of the sorting office over to trenches and hospital beds, interchanging the front doors of British homes as cards begin to pile up and eventually bleeding these contrasting settings into each other to supernatural effect. “One thing that’s really interesting in VR is the idea of locations being on top of each other,” Ashton says. “Firstly you’re in one location, you’re in the trench in VR but you’re also here [in real life], and also the fact that during the experience you cut between different locations, but you’ve not moved anywhere. That idea of a superposition of realities and how you can break down the barrier between those realities is really interesting.”

That basis leads you on a decidedly more existential journey. There’s no explicit visual depiction of the brutality of war shown, but the sometimes-haunting nature of Meredith’s score means its never far from thought. “There is a degree of human connection, but also it is in the middle of an incredibly brutal and horrifying chapter of human history,” Ashton says. “So you can’t escape from it. I suppose we wanted to find a way to be in the war without shying away from the brutal realities of it without visiting those cliches.”

To that effect, Soldiers appear distorted, almost as if made from mist, to reflect the ambiguous, everyman nature of the field cards. “We didn’t want to tell one specific story because we don’t know the story,” Ashton notes. “Taking the idea from the postcard of multiple possibilities; how does that lend itself to narrative?”

The answer lies in the sense of scale Nothing to be Written provides in its short running time. From the sheer number of field cards that flow around you to the eccentric pace in which you phase between locations, the enormity of the conflict and the breadth of people it affected is brilliantly captured. At one point you hold a card up to your face only for it to morph into a sort of muddy window into the reality of the front lines.

“When you received one of those, it would connect you with people in the trenches, but you wouldn’t get a very clear picture,” Ashton says, holding up a card. That’s why people appear as “traces” throughout, and scene changes slowly fade into each other rather than clear cuts. There’s a sense of the murky, unknown reality underneath as if you were trying to create a partly-informed picture of it all in your head that looks past the propaganda 100 years ago.

Despite the scale, it’s a surprisingly intimate and personal piece, emphasized by Meredith’s score that paints each scene with an unnerving sense of foreboding. I felt a sickness in the pit of my stomach at one point as the ghostly figure of a soldier approached to personally hand me a card, like I was about to be given the news I’d always feared even when I had no direct connection to what was in front of me. The human cost of conflict is communicated far better than any VR shooter I’ve yet seen.

Nothing to be Written is going to be showcased at a BBC prom in London next week before doing a round of events and eventually ending up on Oculus Go and other headsets. To me, it’s a piece that showcases why VR needs to start moving beyond its gamified, hyper-violent depictions of war and start bringing us closer to what life was like during real conflicts that shook the world. That’s where this medium’s true power lies.