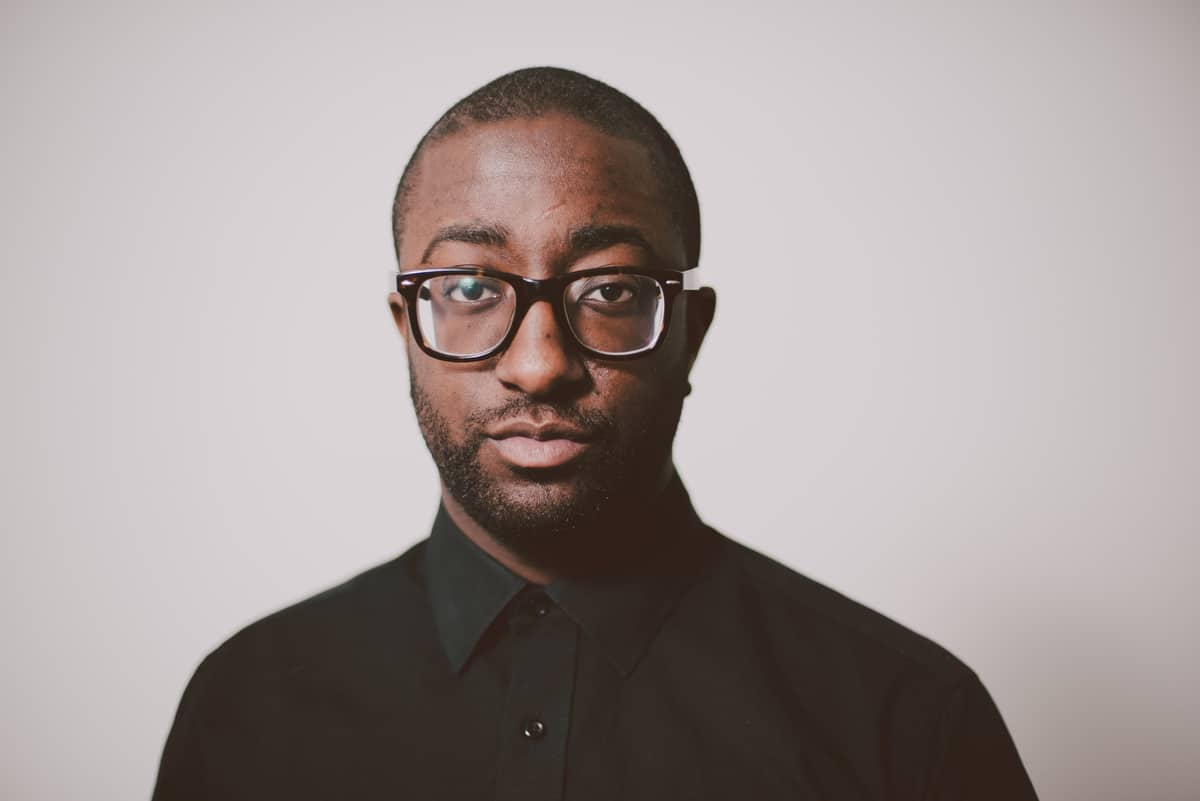

We spoke with the director of Virtual (Black) Reality, Baff Akoto, about how his latest collection of immersive short films tell a connected tale of shared identity.

I wasn’t always a fan of virtual reality. Conceptually, I was on board. It was the practicality of it all – as much as I would’ve enjoyed emulating Ready Player One from the comfort of my home, the associated cost of an Oculus Rift and VR ready PC kept that dream out of reach. And given the fact that VR had come and go multiple times throughout the years, I didn’t think it would last long enough for me to indulge. It had always been a fad.

But, my views started to change as things progressed.

[UploadVR regularly commissions freelance writers to review products, write stories, and contribute op-ed pieces to the site. This article is a feature piece from an established journalist.]

Virtual (Black) Reality: Volume 2

With new technology came expanded uses. I started to see VR headsets as more than expensive toys/machines meant to render virtual worlds for us to play in. I saw them as tools. An avenue to accessible gaming. A means of fighting discrimination. And most recently, a powerful way to connect with others.

This was made most apparent after viewing a narrative VR series called Virtual (Black) Reality: Volume 2. Directed by Baff Akoto (Football Fables, Leave the Edge), the series takes a brief look into the lives of four African-descended Berliners and Parisians.

The goal was to represent black communities that are seldom depicted in mainstream media while also sharing parts of the Afropean experience to others around the world. The shorts do more than that though. They also make aware an undeniable truth. That black people, regardless of origin, have a lot in common with one another.

The idea that we all share a basic level of familiarity isn’t new. As a black person living in the US, this sort of thing is a regular occurrence. Still, I was moved by what I saw in each of Akoto’s short films. It could have been due to my current disposition – 2020 has been a rough year for everyone – or the fact that it was nice to see black people in a state of just being.

But each short resonated with me on a deep level. In them, I found a part of me that I didn’t know was missing. A shared familiarity to unique spaces, some of which I’d had never actually been in. Talking with Akoto, he’d express similar feelings.

“I think it was always a very inherent thing to understand,” explained Akoto over the phone. “That we are global, as black folks, as people or descendants from the African diaspora.”

We are global.

Filmed in 180°, Virtual (Black) Reality was first conceived as part of the YouTube Creators Lab in London back in 2018. The series would eventually land in this year’s BFI London Film Festival as part of the LFF Expanded – the festival’s special grouping of immersive art. Its placement within the festival is a testament to the care that went into each short. Shot in a manner befitting a given subject, the audience is always afforded an intimate perspective on the onscreen happenings. Building on this space are the subjects themselves. Whether it’s Babs in his barber shop or Bella in her dance studio, they all are more than comfortable sharing a part of themselves with Akoto (and the rest of the world).

Outside looking in, Baff Akoto accomplishes his goal – as expressed by him in the details used to explain the series. There’s more to it than just sharing these experiences though. It was also to provide a sense of community. Raised in London and Accra, he didn’t always feel properly represented. Akoto explained that “being African, West African or Ghanaian, was an anomaly [in the UK]. You didn’t really see that representation in the culture. So, from an early age, you kind of pick up that my kind of black wasn’t really mainstream black, ya know?”

The lack of representation wasn’t necessarily indictive of a largely shared sentiment among Afropeans; they weren’t hatful of West African’s or anything like that. On the contrary. The diversity was well met. It’s just that some of us might not always feel as welcome as we should. “You talk to your friends in Germany or your cousins in France and you know, there’s this unconscious kind of multiplicity. Like, this inherent diversity amongst black folks and Africans.” He continued, “but as the same time, [we’re seen] or recognized for being black.”

Akoto wanted to explore the wider context of being black. He didn’t want to focus on our shared trauma though, instead keeping the series grounded in tradition and heritage. “There’s a very well-oiled machine that…kind of commoditizes Black Pain, right? That’s something we are very used to seeing.” I nodded as he talked about how we see ourselves in film. How those works frequent the Oscars. No shade given though. “I mean, they’re very fine projects by very fine filmmakers,” said Akoto. “And I’m not saying I won’t ever do [something like that] but this wasn’t that. This was very much about black life and showing communities.” He wanted to show everyday life.

That’s not to say that his shorts didn’t include any history. One of his shorts featured Kwesi, who works at the Each One Teach One library in Berlin. In it, he shares his views on early German colonial aggression on the African continent. Between 1904 and 1908, German forces would enact the first genocide of the 20th century; they killed Herero, Nama, and San people, sending thousands of them to the first German controlled concentration camps. When I asked Akoto why he included this segment along with the others, given his aim to showcase normal life, he expressed its importance to the culture. “I don’t think we have culture without history, ya know. Like, neither of those things could exist in a vacuum, right?”

Akoto explained that the irrational damage of history is in culture and vice versa. “The Germans have a long and sordid history with colonialism. And if you’re Black and you’re German, that’s something that you need to know and understand in order to kind of make sense of your place in that particular country.” In other words, these shorts mostly offer a peak into the everyday lives of black people. The extra bit of history helps to contextualize their current standing in these countries. “I’m really interested in showing something that wasn’t sensational or headline-worthy,” said Akoto. “Just show another day in the life of people like you or me, you know?”

Virtual (Black) Reality: Volume 2 is profound. On the surface, it might seem mundane. We’re just watching people do their thing? Well, yes. In doing so, we’re allowed to be viewed as normal people. Not the downtrodden. Not slaves. But as black people living our lives. It also showcases a part of the Afropean experience. A view of our culture in Berlin, Paris, London and so forth. Which, with it, comes a realization that we aren’t as different as some would believe. I can see myself rocking with Bella as she incorporates hip hop and African dance into a dope routine, sitting with Kwesi to discuss African history, laughing at Babs’ stories while getting a haircut and encouraging ShaNon as she moderates talks with refugees (utilizing her multicultural experiences).

In a way, they all feel like distant cousins even though I’ve never personally met them or shared in their live experiences – my time living in Frankfert and Berlin, Germany (or the fact that my wife is a first-generation Ghanaian) notwithstanding. “I for one, am always marveling at the spirit around us black folks,” said Akoto. “You have a culture, you know. When you’re stepping into a [black] barber shop in Harlem or one in Paris. You know what…in a sense, you know what you’re going to get.”

We are global.